Cloud Communication

There are a number of different ways for Particle devices to communicate with each other, the Particle cloud, and external services, but this page will focus on the big four: Publish, Function, Variable, and Subscribe.

Logging in

You can interact directly with your device from this tutorial page by logging into your Particle account in the box below. This is optional, as you can use Particle Workbench or the Web IDE and other techniques directly, if you prefer.

Publish

Publishing events is a common thing to do:

- Events are used to publish data from a device to the Particle cloud

- Or from the Particle cloud to one or many devices

- Events are relatively small (622 to 1024 characters; see API Field Limits)

- Events have a maximum publish rate (typically 1 second per event per device)

- Events can trigger webhooks for communicating with external services

- Each event typically uses one Particle cloud data operation

You can learn more Particle publish in the Device OS Firmware API reference.

Publish - simple

This is a simple example that published at a pre-set period. It's configured for 30 seconds, but you

can easily change it. Normally you'd publish something like a sensor value, but for the purposes

of this tutorial there's a fake getSensor() function that just returns a random value so you

don't have to find a special sensor just to run the example program.

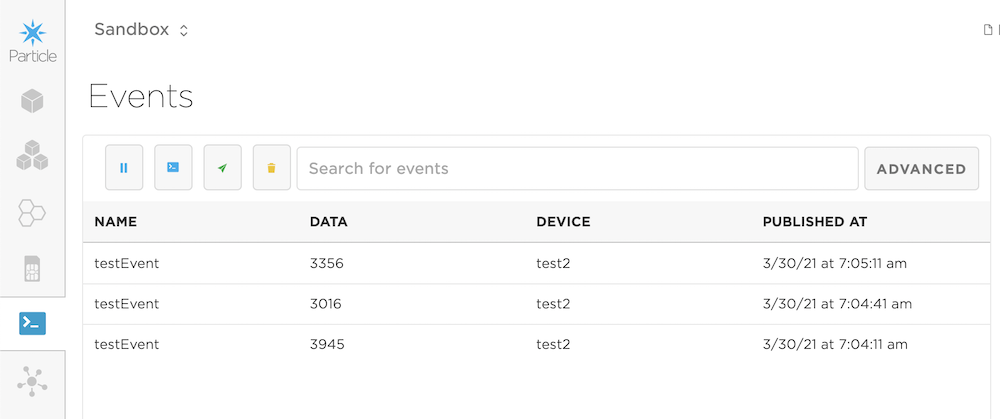

Normally you monitor published events in the Particle Console in the Events tab.

You can also monitor your device right here. Click the Enabled checkbox to view events here.

| Event | Data | Device | Time |

|---|

Within 30 seconds you should start to see testEvent events in the box above if you've flashed the code in the example above.

Deep dive into the code

This is not necessary if you save your source in a .ino file, but it doesn't hurt and it is necessary

if you are using a .cpp file, so I like to just add it all the time.

#include "Particle.h"

This is optional, but the important thing is that it allows your code to run even when not cloud connected. This isn't too important for this example as it just publishes, which can only occur when cloud-connected, but it's still a good idea to get in the habit of using it.

#ifndef SYSTEM_VERSION_v620

SYSTEM_THREAD(ENABLED); // System thread defaults to on in 6.2.0 and later and this line is not required

#endif

This allows USB serial debugging. If you are not seeing debug logs, connecting your Particle device

by USB and using particle serial monitor or a terminal program like screen (on Mac or Linux) or

PuTTY or CoolTerm on Windows will allow you to see the debugging logs.

SerialLogHandler logHandler;

This is a forward declaration. It allows getSensor() to be referenced (in the Particle.publish()

call) before it's implemented at the end of the file. This is not needed in .ino files, but it's

a good C/C++ programming habit to get into.

int getSensor();

This is the event name to publish. You can set it to whatever you want, however:

- Event names are limited to 64 7-bit ASCII characters

- Only use letters, numbers, underscores, dashes and slashes in event names. Spaces and special characters may be escaped by different tools and libraries causing unexpected results

- Event names are a prefix, so code that is monitoring for "test" will also get "testEvent"

const char *eventName = "testEvent";

This is how often to publish (30s = every 30 seconds). Other useful units include min for minutes and h for hours.

std::chrono::milliseconds publishPeriod = 30s;

This keeps track of the last time we published.

unsigned long lastPublishMs;

Nothing to set up in this example, but if you had code to run on each reset or power-up, here's where you would put it.

void setup()

{

}

The loop() function is called periodically, typically 100 or 1000 times per second, depending on the device and other settings.

void loop()

{

We can't publish 1000 times a second, so we use the following construct to only publish every

publishPeriod. We configured it above to be 30 seconds but you can set it anything 1 second or higher.

millis() is the number of milliseconds since the device has booted. You must always set it up exactly

like this: millis() - lastTime >= periodBetweenRuns. The reason is that millis() rolls over to zero

every 49 days, and doing things like trying to remember the next time to run, instead of the last time

you ran, often does not work properly across rollover. This exact construct is always safe across rollover.

// Check to see if it's time to publish

if (millis() - lastPublishMs >= publishPeriod.count())

{

lastPublishMs = millis();

We have a numeric value from our (fake) sensor 0 - 4095. But publishing takes a string, not a

number. This line of code converts the integer value (int) to a ASCII decimal number.

%d is the decimal format specifier. There are many ways other than String::format() but

this technique will come in handy for the next example.

String eventData = String::format("%d", getSensor());

It's good idea to check if you're connected to the cloud using Particle.connected() before

trying to publish an event.

if (Particle.connected())

{

Particle.publish(eventName, eventData);

We also write this to the USB serial debug log using Log.info. This is handy for

debugging problems where you are not getting your events.

Log.info("published %s", eventData.c_str());

We just fake the results here and return a random number here instead of using an

actual sensor. The % operator is the modulus operator, so the value returned

will be 0 <= value < 4096.

int getSensor()

return rand() % 4096;

}

If you are watching the USB serial debug output, you should see something like:

0000030000 [app] INFO: published 3920

0000060000 [app] INFO: published 1524

0000090000 [app] INFO: published 3458

0000120000 [app] INFO: published 1897

0000150000 [app] INFO: published 1172

The leftmost column is milliseconds since startup, and you can see that the publishes are going out exactly in 30 second (30000 millisecond) intervals.

Publish - multiple values

What if you wanted to publish multiple values instead of a single value?

This code is very similar to the last one, except:

Our fake getSensor() function returns two values now, instead of one. Even though the temperature

and humidity are in the function parameters, between the (), they really are "out" parameters that

are filled in by the function.

float temperatureC, humidity;

getSensor(temperatureC, humidity);

Make a comma-separated output of both values. Each value is a floating point number with 1 decimal place %f is a floating point number and the .1 is one decimal place in the float.

String eventData = String::format("%.1f,%.1f",

temperatureC, humidity);

You could change the code to be %.2f or %.0f and you could probably guess what would happen.

The USB serial debug output for this version looks like this:

0000030000 [app] INFO: published 38.0,24.7

0000060000 [app] INFO: published 33.8,56.6

0000090000 [app] INFO: published 18.3,37.9

0000120000 [app] INFO: published 9.0,98.4

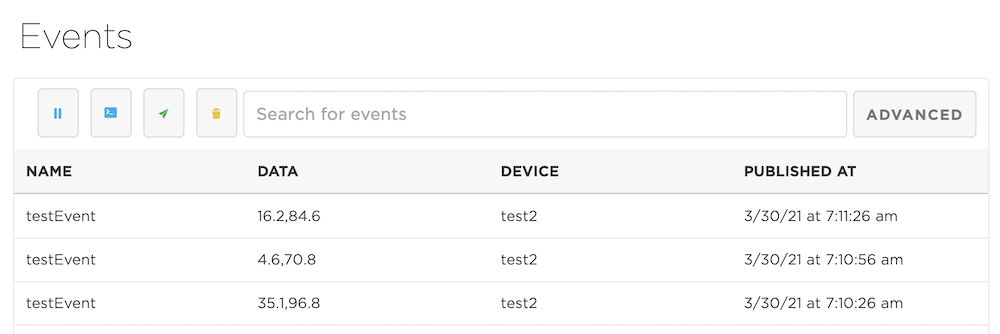

And in the console:

Publish best practices

- Rate limit your publishes. If you exceed the rate limit average of 1 per second the events will be discarded.

- Check for cloud connectivity before publishing for best performance.

- If you have timing-sensitive code in your loop, you may want to publish events from a worker thread in the background.

- Efficiently using publish can save on data operations.

Function

- Functions allow the cloud to call one device to perform a task with optional data

- Function data is limited to 622 to 1024 bytes of UTF-8 characters; see API Field Limits

- You can have up to 20 functions per device, but you can also use the data parameter to handle many more variations

- Functions can only return a 32-bit integer value. They cannot return strings, double width floating point, etc.

- Functions only work when the device is online and breathing cyan

- Each function typically uses one Particle cloud data operation

Maybe a table will help:

| Publish | Function |

|---|---|

| One-to-many | One-to-one |

| All devices in account can subscribe | Function only goes to one device |

| No delivery confirmation built-in | Function returns an integer value |

You can learn more Particle functions in the Device OS Firmware API reference. There is also another tutorial in Blink an LED over the net.

And a few notable limits:

- Up to 15 cloud functions may be registered

- Each function name is limited to 64 characters

- Only use letters, numbers, underscores and dashes in function names. Spaces and special characters may be escaped by different tools and libraries causing unexpected results.

- A function callback procedure needs to return as quickly as possible otherwise the cloud call will timeout.

- You should not call

System.reset()from a function handler. Instead set a flag and callSystem.reset()fromloop(). The reason is that if you reset from the function handler, the system will reset before the function handler return is sent back to the cloud, so the command will always time out, even if it successfully reset the device.

Function change LED color

The USB serial debug log might look something like this:

0000090450 [app] INFO: setColor 0,0,255

0000090450 [app] INFO: red=0 green=0 blue=255

0000100450 [app] INFO: reverted to normal color scheme

Code details

This constant determines how long to keep the custom color before reverting back to the Particle color scheme (typically breathing cyan). In this case, 10 seconds.

std::chrono::milliseconds colorExpirationTime = 10s;

This is the code that actually reverts:

if (colorSetTime != 0 && millis() - colorSetTime >= colorExpirationTime.count())

{

// Revert back to system color scheme

RGB.control(false);

colorSetTime = 0;

Log.info("reverted to normal color scheme");

}

This is the handler for the setColor Particle.function. It prints the input cmd to the

USB serial debug log.

int setColor(String cmd)

{

int result = 0;

Log.info("setColor %s", cmd.c_str());

It uses sscanf to read the single string containing three decimal numbers separate by commas

into three separate int values.

If parsed successfully, it uses the Device OS RGB functions to override the LED scheme and returns 1.

int red, green, blue;

if (sscanf(cmd, "%d,%d,%d", &red, &green, &blue) == 3)

{

// Override the status LED color temporarily

RGB.control(true);

RGB.color(red, green, blue);

colorSetTime = millis();

Log.info("red=%d green=%d blue=%d", red, green, blue);

result = 1;

}

If it does not parse it returns 0.

else {

Log.info("not red,green,blue");

}

return result;

}

Other experiments

What happens if:

You call a function with a different name, like

setColour? Or just a different case likesetcolor?You send a

setColorbut only send255,0instead of255,0,0? What happens to the return value?You send up something completely unexpected like

tacofor the command argument?You have spaces in the function argument like

0, 255, 0?

Variable

- Variables allow the cloud to call one device and ask for a value

- Variable data is limited to 622 to 1024 bytes of UTF-8 characters; see API Field Limits

- You can have up to 20 variables per device

- A variable can contain multiple values if encoded (comma separated values, JSON, etc.)

- Variables only work when the device is online and breathing cyan

- Each variable retrieval typically uses one Particle cloud data operation

| Publish from Device | Variable |

|---|---|

| Device says, "here is my value." | Cloud asks "what is your value?" |

| Cloud gets value even if no one cares | Value is only sent when requested |

| Value can only be retrieved when device is online |

You can learn more Particle variables in the Device OS Firmware API reference.

Variable normal

The normal use of variables is to first create a global variable:

int sensor;

Then, in setup(), link a cloud variable name "sensor" with the variable itself, sensor. In this case they're named the same, but they don't have to be.

Particle.variable("sensor", sensor);

With variables, you can update the global variable sensor as much as you want. It will only use data operations when the value is retrieved from the cloud.

Also, you almost never call Particle.variable() from loop(). You call it from setup() to let the cloud know you have a variable available, not the the value changed! If you need to tell the cloud when you change a value, you should use publish instead of variables.

Because we need to update sensor periodically, we do it from loop(), every second:

if (millis() - lastSensorCheckMs >= sensorCheckPeriod.count())

{

lastSensorCheckMs = millis();

sensor = getSensor();

}

You can get the value of the variable here:

- Or in the console

- Using the Particle CLI:

particle get test2 sensor

Variable calculated

One thing about the earlier example: We continuously read the sensor even if the cloud isn't asking for the value. Sometimes you want to do this, for example if you are averaging values. But sometimes you might want to retrieve the value on demand only.

Fortunately, this is really easy to do. Instead of passing a global variable to Particle.variable you can pass a C++ function call!

int getSensor();

void setup()

{

Particle.variable("sensor", getSensor);

}

int getSensor()

{

// To make this tutorial function without actually

// requiring a sensor, we just return a random

// value from 0 - 4095 like you'd get from an

// analogRead() call

return rand() % 4096;

}

The function must return one of the allowed types: int, bool, double, or String.

Subscribe

- Subscribe allows the cloud to send a message to many devices

- Publish data is limited to 622 to 1024 bytes of UTF-8 characters; see API Field Limits

- You can have up to four subscriptions per device, but it's a prefix so you can accept many events with one subscription

- Subscribe only works when the device is online and breathing cyan

- Each event received typically uses one Particle cloud data operation

- There is no confirmation built-in: the publisher of an event won't know if a specified device receives it

You can learn more Particle subscribe in the Device OS Firmware API reference.

This example works like the function example, except it uses subscribe instead of functions.

- Or in the console

- Or using the Particle CLI:

particle publish setColor "255,0,0"

The main differences are:

- If you flash this firmware to multiple devices in your account they all change at once!

- You can't tell if a device actually received the change request

It is possible to handle confirmation of event received; it would require that your device publish an event that it has received the event, and then the cloud would have to keep track of which devices received the event.

Device subscribe

While there's no ability to force an event to go to only one device, you can use the event prefixing capability to emulate this behavior.

In this example, the subscribe is prefixed by the Device ID:

Particle.subscribe(System.deviceID() + "/setColorEvent", setColor);